?[Gasoline] taxes do not properly price roads, with the result that traffic congestion costs Americans close to $200 billion per year?. Congestion pricing can ? nearly double actual road capacities during rush hour, from 1,000 to 2,000 vehicles an hour.?

Gasoline and diesel fuel taxes have long been the main source of funding for building, maintaining, and operating America?s network of highways, roads, and streets. This is why the American Petroleum Institute nearly a century ago?worked to enact such levies, welcoming taxes on its product to enable systemic road building to increase the demand for its chief product.

Today?s motor-fuel taxes are, at best, an imperfect user fee. One problem is that inflation and increasingly fuel-efficient cars have rapidly eroded gas tax revenues. After adjusting for inflation, drivers today pay only a third as much for each mile they drive as they did in 1956, when Congress created the Interstate Highway System.

Raising the pump tax would alleviate this problem, at least temporarily. But it won?t fix its other problems. The biggest is that gas taxes do not properly price roads, with the result that traffic congestion costs Americans close to $200 billion per year.

Another problem is that gas taxes are collected mainly by the federal and state governments, and local governments must find $30 billion in general funds each year to maintain county roads and city streets. As a result, local roads and bridges tend to be in poorer condition than highways funded out of user fees.

My New Study

On May 14, the Cato Institute published my new paper, Ending Congestion by Refinancing Highways, which made a case that replacing gas taxes with vehicle-mile fees could solve all of these problems. Such fees would be flat on uncongested roads and vary with the amount of traffic on congested roads.

The paper argues that congestion pricing is particularly important for highways, which are the only resource whose supply actually declines when demand increases.

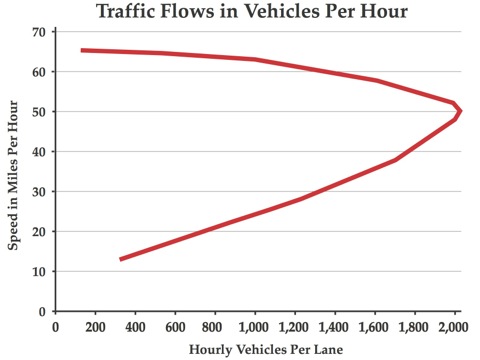

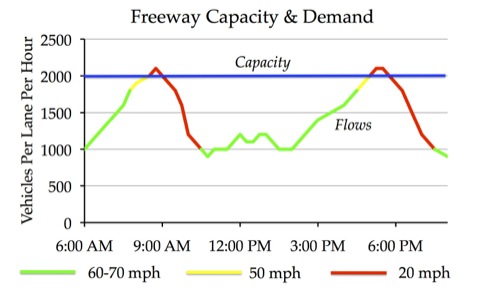

A typical freeway lane can move about 2,000 vehicles an hour in free-flowing traffic, but when the road becomes congested, traffic flows can decline below 1,000 vehicles per hour. Even if traffic demand exceeds 2,000 vehicles an hour for only a few minutes, stop-and-go traffic can result for hours until demand falls below 1,000 vehicles per hour. Congestion pricing can therefore nearly double actual road capacities during rush hour, from 1,000 to 2,000 vehicles an hour.

While economists have long understood the benefits of congestion pricing, some people object to converting highways that are now ?free? into congestion-priced roads, fearing they are being charged twice to use the same roads. The Cato paper answers this objection by proposing to eliminate gas taxes, thus eliminating any fears that people are being charged twice.

Experiments with vehicle-mile fees in Oregon have shown that it is possible to collect such fees without invading traveler privacy. A GPS or similar device on board a vehicle keeps track of how much drivers owe and reports this to a specially equipped gasoline pump when the driver fills up the car?s tank. The amount of payment could be broken down by road system?state, county, city, or private?but otherwise the device would not report when or where the car went on various roads.

The state estimated that the system it used could be installed on all gasoline pumps in Oregon for about $33 million and that the cost of GPSs would be about $100 per car, though that cost could decline with advances in technology and mass production. The system wouldn?t have to use dedicated GPSs; it could use smart phones, transponders, or other common devices.

A recent report?from the Congressional Budget Office concluded that automobile fuel efficiency is growing faster than driving, meaning that gas tax revenues will steadily decline. Given this, the transition to vehicle-mile fees is inevitable. However, the faster that transition takes place, the sooner we will be able to relieve traffic congestion and fix other inequities with highway funding.

As such, Congress and the states should take action to rapidly transition from gas taxes to more efficient vehicle-mile fees. Any state can take the lead by switching from gas taxes to mileage-based fees, but as more states switch, they will need to coordinate to make sure their systems are compatible with one another. One side-effect from the switch will be a devolution of transportation funding from the federal government to the state and local level, which will depoliticize many transportation decisions.

Graphics

The maximum flow capacity of a typical freeway lane is about 2,000 vehicles per hour. However, when demand exceeds that capacity, flows fall to 1,000 vehicles per hour or less, cutting traffic flows in half as seen in Figure 1.

Even if traffic flows exceeds the maximum flow capacity of a highway for only a few minutes, the resulting decline in flows can lead to hours of stop-and-go traffic, indicated by the red line in Figure 2.

james harrison james harrison falcons giants game norman borlaug santorum new hampshire debate

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.